Few cities in the world have modernized faster than Kathmandu Valley. Modern cities have ravaged rich agricultural land, drained wetlands and ponds, eaten open spaces, enclosed public spaces for profits, and flooded the city space with high buildings and shopping complexes.

Giant shopping complexes close to a dense city not only destroy the traditional urban fabric but also the environmental service-givers like water fountains, ponds and open space. Ponds are the most encroached and neglected in the cities, despite having significant environmental, cultural and historical value.

Today, Naag Pokhari of Sundhara and Kamal Pokhari of Thamel exist only in our memories. Modern shinny buildings with underground parking space – Civil Mall and Chhaya Devi Complex – have swallowed these ponds.

From Pokhari to Mall

In 2010, Civil Mall opened with much fanfare. Promoted as a mall with movie theaters, shining lights and fancy shops, it masked a 200-year history.

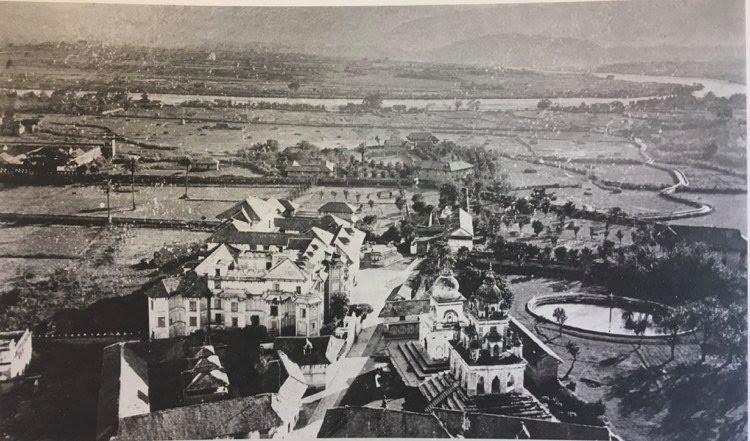

After 1769, the area of Sundhara extending from Dharahara up to the Central Jail used to be a single walled compound with a mansion. In The Blood Stained Throne, historian Baburam Acharaya writes that the mansion belonged to Balbhadra Shah, descendants of Prithivi Narayan Shah’s second brother. When the Thapas and Ranas rose to power between during 1820’s – 1951, they built palaces and many monuments nearby.

In 1823, after Balbhadra Shah’s death, Bhimsen Thapa forcefully occupied the mansion. For the first time ever, he built a palace with a garden known as Janarala Bag with ponds and temples. Today, Only the two dome-shaped temples – Ramchandra and Bhimmukteshwor – stand. In 1940, after the 1934 earthquake destroyed the palace built by Bhimsen Thapa, Hari Sumsher constructed a new palace named Hari Bhawan.

Within the premise of Baag Durbar complex another pond named Naag Pokhari was present towards Tundikel side along with a small temple of Naag. Later this small shrine was shifted to the other side of the road, next to Tudikhel. Where once a natural water body stood, today the shining Civil Mall stands as a proof of the modern city. Naag Pokhari stood with water until the 1970s (as seen in picture). In the 2000s Civil Mall was constructed, bulldozing the remains of the Pond. Baag Durbar’s lands were fragmented and sold; only the main building remains, which is now under Kathmandu Metropolitan City.

After the 2015 earthquake, when Kathmandu Metropolitan City proposed demolishing Baag Durbar to construct a new building, the public erupted in protest. This was good but the people overlooked something important: it’s not just Baag Durbar but the whole surrounding area that is historically important with numerous scattered monuments – Dharahara, Sundhara, Ramchandra, Bhim Mukteshwor temples. Many people have forgotten Naag Pokhari.

The gate in Baag Durbar used to open for the public once a year. Old people remember passing through Baag Durbar for the Upaku ritual during Indra Jatra. On that day, the families of those who have died that year walk around the ancient city boundary, placing butter lamps along the way. The ancient route passed through Baag Durbar, which opened from the Dharahara side leading to Gana Bahal. Some elderly people remember beautiful gardens with ponds and guards guarding the palace. Now cars and motorbikes whizz through numerous fragmented properties of Durbar complex sold over time.

From the time of Prithivi Narayan Shah, this place was home to Royals and Nobles because of close proximity to Hanumandhoka Royal Palace. Despite its historical importance, temples and palaces were left to ruin, while the pond was replaced by a fancy shopping mall. Now not even traces of the pond remain.

From Pokhari to Complex

More recently, in 2018, another shopping mall opened after burying a swampy pond: Chhaya Devi Complex on Kamal Pokhari. Many locals remember this place as a pond with lotus, trees and stupas. Because of lotus grown on this pond, it was named Kamal Pokhari (or Paleswa Puku in Nepal Basha).

For generations until 1920, Kamal Pokhari belonged to a Buddhist monastery named Tham Bahi or Dharmadhatu Mahabihar or Vikramasila Mahabihar or Bhagwan Bahal, which sits in front of Chhaya Devi Complex. Tham Bahi is one of the important Bahi of Kathmandu. Thamel – the surrounding area is the corrupted word of Tham Bahi.

Kamal Pokhari was an endowment for Tham Bahi Guthi which helped in sustaining the Guthi functions. Most of the temples and monasteries within Kathmandu Valley had land endowment to generate money for the upkeep of temples and rituals. Bhagwan Bahal Guthi used lotus flowers and leaves grown in Kamal Pokhari for temple rituals, and sold while the extra remaining were sold. Chhaya Devi Complex erased the traces of the pond, along with its religious connection to Tham Bahi.

In 1920 Keshar Sumsher used political power to capture the pond and its land into the Keshar Mahal compound. In return, he pledged to provide the guthi with 125 rupees yearly. He never paid more than once. Later this property went to Keyur Shumsher and then to his wife Ambika Rana. Prithivi Bahadur Pandey bought it, then built Chhaya Devi Complex in 2013.

Fragments of Bahi still remain — towards the entrance of the shopping complex near the street, three Medieval Chaityas with images of Pranjaparmita, Aksobhya and Amitabha sit in a brick base. A Larger Chaitya built much later stands behind the smaller ones. At the back bordering the wall of the complex stand Saraswoti temple and an important stone. According to the locals, the stone was brought from Kashi. Local people still throw the sacred remains of shraddha on that stone.

Guthi members of Tham Bahi performed an annual festival of Chhaka Dhyo on raised platform towards the entrance of the complex. According to the local resident Bhagwat Narsing Pradhan, even the raised platform is now registered as private property. In his book Buddhist Monasteries of Nepal, John Locke mentions a long Falcha on this side, which has now disappeared.

There used to be numerous ponds all over the Valley. Kamal Pokhari is one of the few with documented evidence. Locals still remember and tell stories associated with it. Despite this, the community was unable to protect the pond from the power of greed. Local people continue to struggle to regain the lost property.

Astha Narayan Maharjan, a 90-year-old resident of Tham Bahi, remembers the pond to be smaller than Rani Pokhari, full of water, lotus flowers and leaves. Local people used to wash their faces before paying homage in Bhagwan Bahal. People used water from the pond for all the rituals. The excess water from the pond flowed towards the south.

Constructing malls over ponds not just erases cultural and historical associations but also destroys the environment. As habitat for flora and fauna, ponds also recharge ground water. Modern education overlooks the traditional knowledge behind these city ponds. We were not able to understand the environmental values of ponds. Many ponds have disappeared over the last few decades.

People living in the periphery of the ponds failed to preserve the traditional water sources. Neither were the government’s laws enough for the conservation of ponds. Instead of safeguarding, the government set a precedent by destroying the ponds for its own greed. It destroyed a pond to make the Sanchayakosh building in Thamel and Lalitpur Metropolitan City office in Patan.

We have collectively killed many of Kathmandu’s ponds but we can still save the remaining few. Kamal Pokhari, Ikha Pukhu, Saptapatal Pokhari need urgent safeguarding before it’s too late.