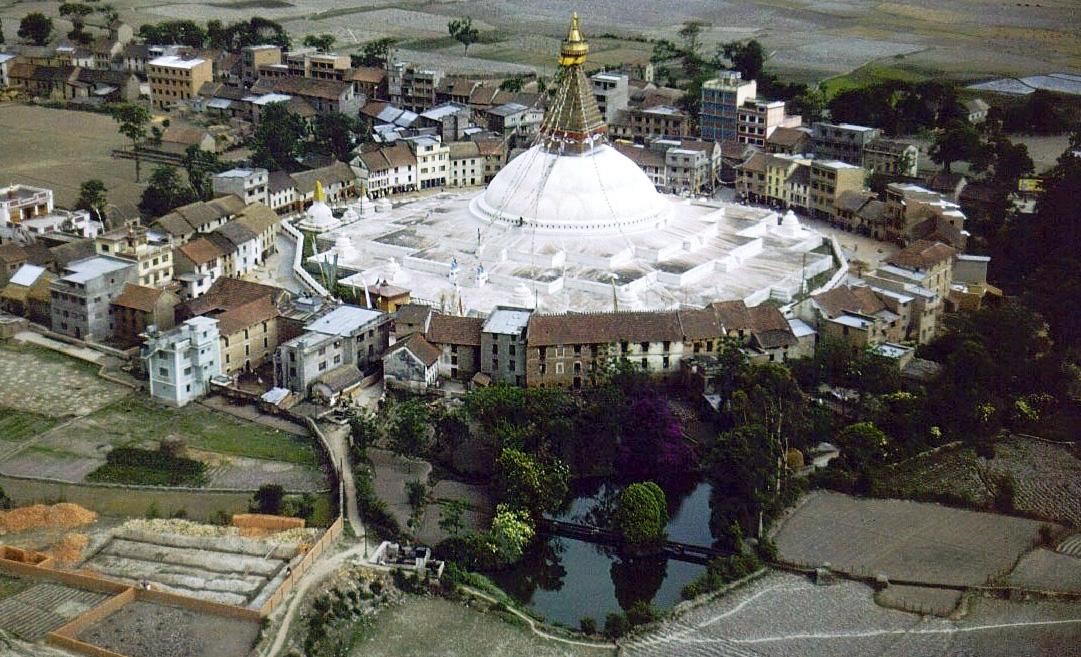

Many of veteran photographer Mani Lama’s most iconic images are that of the Boudha stupa, which often end up as postcards. This is no surprise, as Lama was born in Boudha.

“I used to live right in front of Boudha. Trees used to surround Boudha,” recalls the 74-year-old Lama.

Lama is able to trace his lineage back to the “60 ghare Tamangs” — the 60 Tamang families who have lived around the Boudha stupa for generations. And in the many decades of his life, Lama, along with other old residents of the area, has witnessed the gradual changes to the Boudha of his youth.

“While growing up, I remember my uncle, a colonel in the Nepal Army, came home. He had learned fish farming. One day, he went to the Ghyoilisang pond and blocked one end for the whole night. He filled the pond with fish as the water level rose and started selling those fish. It was quite a lucrative business,” says Lama.

Hile macha, or catfish, were plentiful in the pond, which gets its name from the Tamang language — ‘ghyoi’ meaning pond and ‘lishang’ meaning backyard. Freshwater birds like bakkula (egrets) used to swarm the pond water.

Fifty-eight-year-old Bishwa Maskey too grew up alongside Lama in Boudha and has the same fond memories.

“I used to catch fireflies on the way from Boudha to the Bagmati river,” he recalls.

But both Maskey and Lama agree that Boudha has changed.

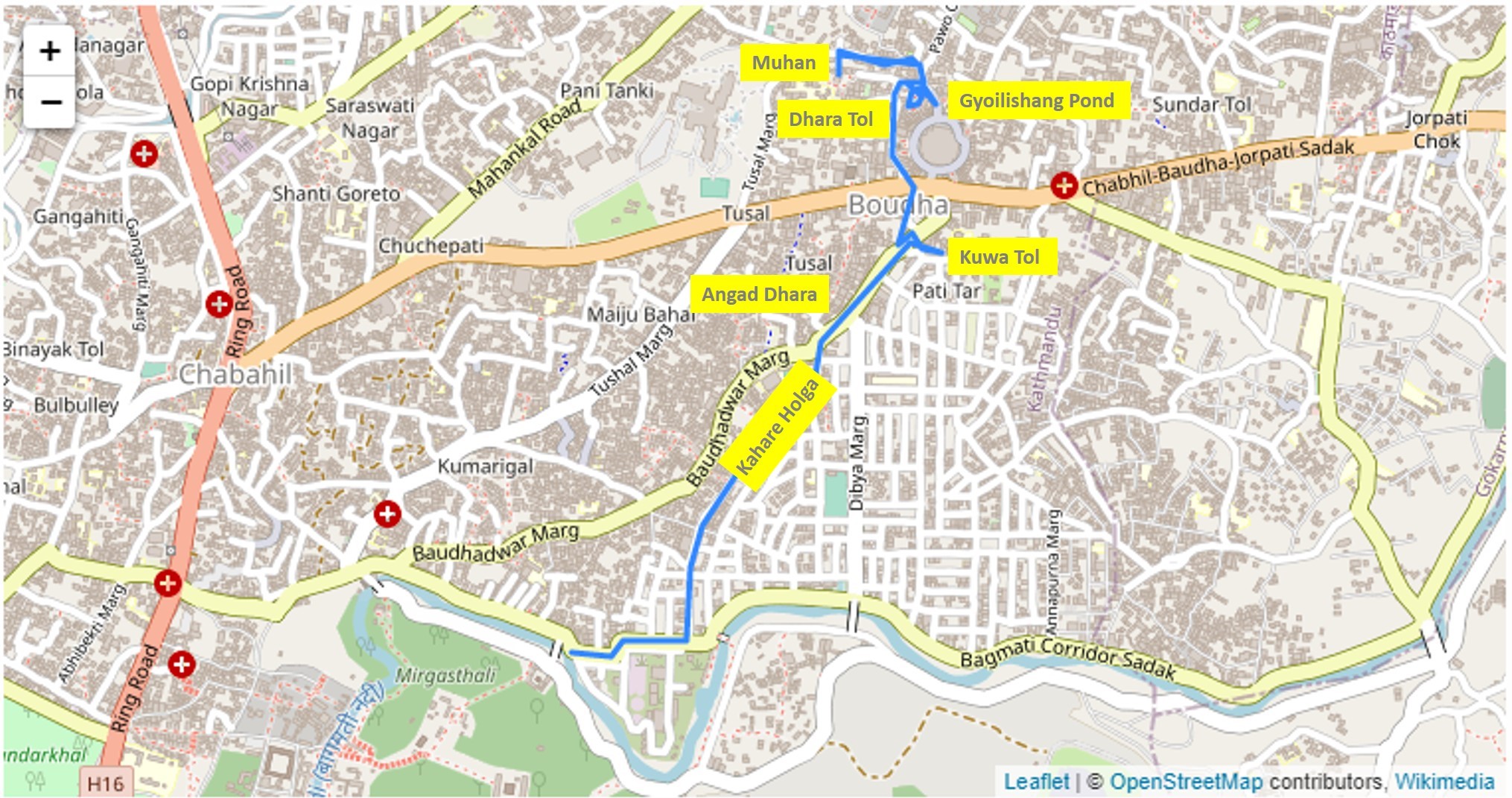

The excess water runoff from the Ghyoilisang pond used to meet a seasonal stream called Holga, but that stream has become a sewage canal. With hundreds of new concrete houses springing up and the streets all paved, water could not percolate and keep the pond fed. Now, the Ghyoilisang is dead and gone, even though the area around the pond is now called Ghyoilisang Marg. Tourist guides bring visitors to a statue of Guru Rimpoche to show where a ‘historic’ pond once used to be.

Boudha’s aquatic history

Every morning, devotees to Boudhanath Stupa offer prayers with fresh flowers, rice grains, and plastic water bottles. Each day, they replace old plastic bottles with new ones. This practice of offering water to Boudhanath is the continuation of a decades-long tradition where people offered fresh spring water.

As such traditions and stories illustrate, Boudha has an intimate relationship with water. The Newa community calls the stupa khastey — ‘khas’ meaning dew and ‘tey’ meaning drop. Purna Devi Maskey, a 78-year-old Boudha resident, says that dew drops collected and squeezed from a piece of cotton cloth helped construct Boudha Stupa. A 2012 survey by the anthropologist Mukta Tamang identified 35 water fountains, 11 wells and five ponds in Boudha, although a quarter of them were dry.

Tamang, who lives near Boudha, writes in his paper, Water Connection: Everyday religion and environments in Kathmandu Valley’ that the interdependence of land and water gave birth to Boudha’s rituals, festivals and practices. The agricultural land, irrigation, forests, and livestock were important elements of daily practice and added meaning to the elements of worship. These practices helped communities learn about and sustainably manage their surrounding environment.

One such ritual is the Mamla Jatra where Boudha residents worship Ma Ajima, protector-goddess of the Boudha stupa. During the full moon in January-February, men carry the deity in a palanquin around the periphery of Boudha and Newa families make offerings of duck eggs, along with rice and flowers.

The duck eggs illustrate Boudha’s relationship with water. Due to the close presence of wetlands and ponds, ducks were bred by the Jyapu community. But this trend of offering homegrown duck eggs is changing. These days, Newa residents of Boudha simply purchase duck eggs from the market to offer to Ma Ajima.

“Now that many of the water sources have dried up, been abandoned, or destroyed for the construction of modern buildings, peoples’ access to gods for requesting help and blessings has been severely restricted,” writes Tamang.

A 19th century thangka painting too celebrates Boudha’s relationship with its surroundings. It displays gods, rivers, mountains, animals, and humans with the lower right section of the thangka mapping the flow of water around the stupa. A stone waterspout in the upper right corner shows a water source shared by local communities flowing into a small pond. Tamangs call that waterspout Mangbala waadi, meaning second dhungedhara in the Tamang language. In the thangka, a woman collects water from a well above a waterspout adorned with a serpent king seated on a snake-like coil. That waterspout was the Tongbala waadi, which means first dhungedhara. The thangka also shows the Ghyoilisang pond.

Forgotten springs

In Nepali, khahare khola refers to a perennial monsoon stream. Such streams are essential because they drain excess water from the land during the monsoon season into the rivers.

In the 1970s, many khahare kholas would flow from Boudha to the Bagmati river. Marshlands and ponds rested alongside the streams. Old residents recall the monsoon rains lasting for many days, unlike few hours of rain in current times. During the monsoon, when 90 percent of the year’s rain falls, ponds like Ghyoilisang became the area’s storage systems. Natural water storage replenishes water towers like the Kapan forest. Draining excess water from Ghyoilisang pond, the khahare Holga (which, in Tamang, means a stream flowing from the back) flowed under a phatke, a temporary bridge, towards the marshlands (pawwa) to connect to the Bagmati in Guheshwori.

The 1990s saw a real estate boom in Boudha, as much of its agricultural lands were converted to commercial real estate. Fields turned into concrete houses; streams turned into streets; and rivers turned into roads. The khahares were converted into sewage drains that follow the same routes, meeting the Bagmati at the Guheshwori confluence for water treatment. The overburdened water treatment plant at the confluence refines Boudha’s sewage water and dumps it into the Bagmati.

In the monsoon season, the Holga now floods the roads. Mukta Tamang indicates that the Kathmandu Metropolitan City’s failure to “regulate uncontrolled construction of modern buildings” has resulted in unmanaged sewerage and drainage systems, along with river and water pollution. Very few residents seem to realize that the water flooding the roads or entering their shops is the khahare Holga.

But the Holga has long been forgotten by many of Boudha’s current residents, much like many of the other water sources in the area.

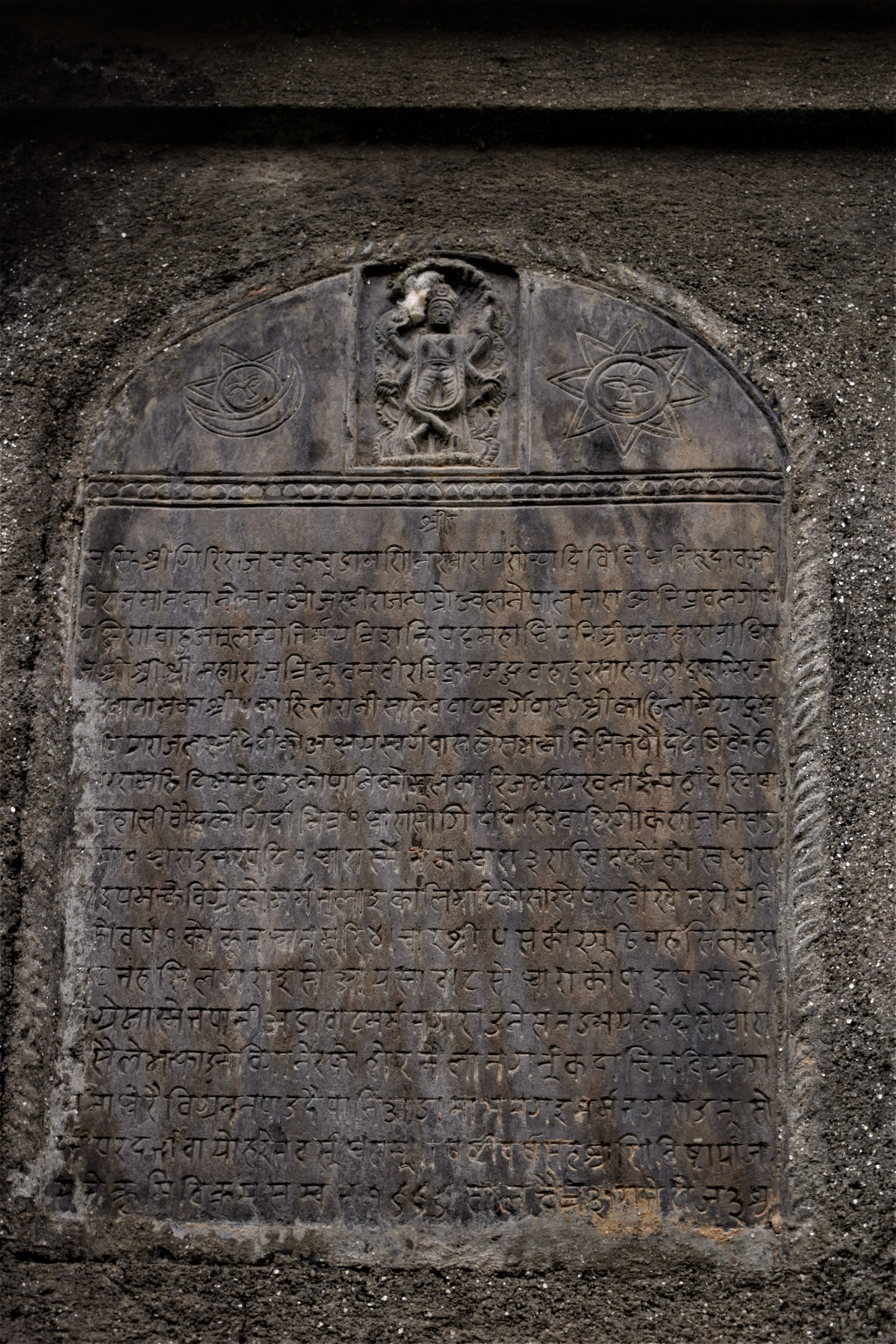

Sixty-four-year-old Boudha resident Tashi Lama’s father used to tell him about the arrival of a queen on a palanquin to Boudha. The queen was the Kahila Rani, or the fourth queen, as in the fourth wife of king Tribhuvan and she consecrated a spring to the north of Boudha. A stone inscription that still stands by the spring mentions the consecration of water taps by “Shree 5 Kahila Rani Saheb (1943 March 17 AD Wednesday) in the memory of a deceased fourth daughter.”

The queen reportedly built a shed and three additional taps — one within the periphery of Boudha, another towards the Gokarna side, and the third on the northern side of Boudha. A patch of paddy land was dedicated to these dharas under the control of the local Guthi to generate costs for upkeep and maintenance. Strict instructions were given to keep the area clean.

“People in the olden times never used cement. They used local mud – surki (raw lime, lentils with molasses) for construction,” says Tashi Lama.

In the 1980s, the Nepal government began to supply water to Boudha from Sundarijal forest, about 13 kilometers away from Boudha. Gradually, residents forgot local sources of water like this spring. Elderly locals say that the muhan provided water for both the Tongbala and Mangbala waadi. As these stone spouts lie a few steps away from one another, locals call the area Dhara Tol.

Currently, high brick walls barricade this spring, which has been all but abandoned.

“This is centuries-old land and no one can encroach on it or misuse it,” says Tashi Lama. “The sole responsibility belongs to the government — whether they want to rebuild it, modify it or destroy it.”

Prior to the 1980s, Boudha women would fetch water from Dhara Tol and Kuwa Tol, which lies a kilometer-and-a-half south of Boudha and hosts three wells. Women would line up at these dhungedharas and kuwas to drink water, and wash their clothes and dishes. Sometimes, these gatherings would erupt in conflict. There was even a saying, “If you want to see women fighting, go to Dhara Tol’, says Mani Lama.

But as the city grew, demands for water began to rise. The rapid rural to urban migration during the mid-90s in the midst of the Maoist conflict further intensified demands. From the late 1990s, hotels and wealthy Boudha residents began to demand more water. By 2010, more than 50 percent of Kathmandu’s agricultural land had been lost to urbanization, according to Tamang’s paper. Population density doubled in just a decade from 2,739 per sq km in 2001 to 4,416 per sq. km in 2011 in Kathmandu district, according to 2011 Population and Housing Census.

The Kathmandu Upatyaka Khanepani Limited (KUKL), a public company responsible for water supply in the Kathmandu Valley, was unable to meet this demand, leading many to install boring machines and pumps.

By the late 2000s, excessive extraction of groundwater through boring machines had depleted the water table, writes Tamang. This resulted in the drying up of the dhungedharas and kuwas, which turned into garbage dumps. Not only was ground water being extracted at uncontrolled rates but it was also not being replenished as concretization of the land did not allow rainwater to percolate into the earth. Ground water extraction reached 21.56 million cubic meters per year in 2016, exceeding the recharge rate of 14.6 million cubic meter per year, according to Tamang. In less than 100 years, Kathmandu valley aquifer reserves are expected to deplete.

“We dug out water from the earth but water from the sky was not able to go back into the earth,” says Tashi Lama.

Now, the dhungedharas of Dhara Tol are called kaldharas as a tap has been attached to the spouts. The water for these kaldharas does not come from a spring but rather, through boring or via a water reservoir established by the city authorities.

Water reservoirs have sources like Sundarijal and Melamchi, which are 13.7 km and 38.7 km away respectively. Earlier, locals had access to nearby spring water, but now, the water comes from farther and farther away.

During his teens, Mani Lama remembers dense bamboo groves growing on the grounds of White Gumba. A koiralo tree stood next to the bamboo and in the 50s, monks from nearby monasteries would use the bamboo to construct temporary sheds for death, marriage, and prayer ceremonies. Hindu pundits plucked koiralo flowers for their rituals. But now, both the koiralo tree and the bamboo groves have disappeared.

Water is personal

Boudha’s connection with water goes deeper than what meets the eye.

According to Khadgajit Lama, president of the Boudha Kalyan Guthi, freshwater is sprinkled over one’s head after a family member’s death to purify oneself before entering the home.

Water is not just a resource but a part of social exchange. Water is cultural and culture is personal.

In the 1980s, Boudha’s Buddhist cemetery, situated near the northern gate, was moved two kilometers below Boudha while widening the road from Boudha to Jorpati.

Soon after the shift, Khadgajit Lama remembers attending a death ceremony in the new area.

“Angad dhara was the closest water source to the new cemetery. But that dhara had dried up and there was no water for us to sprinkle after the death ceremony,” he recalls.

Khadgajit and other locals attempted to revive the Angad dhara but soon realized that all the nearby sources of water, which used to recharge the aquifer that supplied the dhara its water, had dried up too.

“Boring water became a solution to the crisis. The earth was drilled, water extracted via a pump and supplied through a pipe to the dhara,” he said. “Now, an electric switch determines the flow of water from Angad dhara.”

Water spouts like the Angad dhara reflect the social, spiritual, and cultural links among Boudha’s communities. The role of everyday religion for urban sustainability is pivotal, writes Mukta Tamang.

“The people’s affective connection to water could furnish the political will for better water management,” he writes.

Urbanization has profoundly shaped the ecology and the rhythm of social exchange patterns. Tamang observes a sense of loss amongst Boudha’s old residents. Tamang asks, “If water has the power to clean us, do we have the power to restore, reclaim and revive these water resources?”

Water links nature with religion and can be a vehicle for collective social action. But, the importance of water has been undermined, despite its role in shaping and reshaping Boudha’s legacy. But these links surface whenever there is a rupture, however big or small, in the manner in which these links operate.

As in the case of 46-year-old Kanchi Tamang, who misses the taste of dhara water. She complains about the high iron content in the boring water and how cannot brew her raksi with that water.

In the 1970s, the establishment of new carpet factories in the Kathmandu Valley pulled 21-year old Kanchi Tamang from Sindupalchok to Boudha. She spent 25 years in Dhara Tol, weaving carpets. As she didn’t have time to collect water in the mornings and evenings due to her work, the factory drilled its own boring well and began to provide water to its workers, a practice that many carpet factories in the area adopted.

Similarly, Ram Bahadur Bayalkoti, 52, has lived all his life in Kapan. He recalls having to wait to get access to water from a common kuwa until his ‘upper caste’ neighbors had finished their morning rituals.

One day, while grazing his cows, Bayalkoti found water oozing out from the crevices along the pathway of a khahare khola.

“Ah! That water was so sweet. There were no pipes then, so we used to slash some bamboo and allow water to flow through it” he says.

For him, the discovery of that water source was a godsend. Bayalkoti is from a pani nachalne jaat, so-called ‘untouchable’ castes from whom others do not even accept water.

“Access to water symbolizes class status in today’s Kathmandu,” writes Tamang.

In Boudha’s private schools and hotels, boring machines provide easy access to water. But Boudha’s public schools suffer from a lack of proper drinking water. In many such schools, muddy brown water emerges out of the drinking water taps as these institutions cannot afford sophisticated water filtration systems.

During lunchtime, children leave their school compounds to drink water and many of them do not return. Teachers complain of a lack of attendance after lunch while parents like Kanchi Tamang complain of their children developing stomach ailments or headaches due to the poor water quality in school. With the summer heat, children even suffer from dehydration due to a lack of drinking water.

A high-end water filtration system costs around Rs 100,000. Ironically, these systems use pebbles, sand, and charcoal to filter the water — the same materials that water naturally flows through.

Water has its way

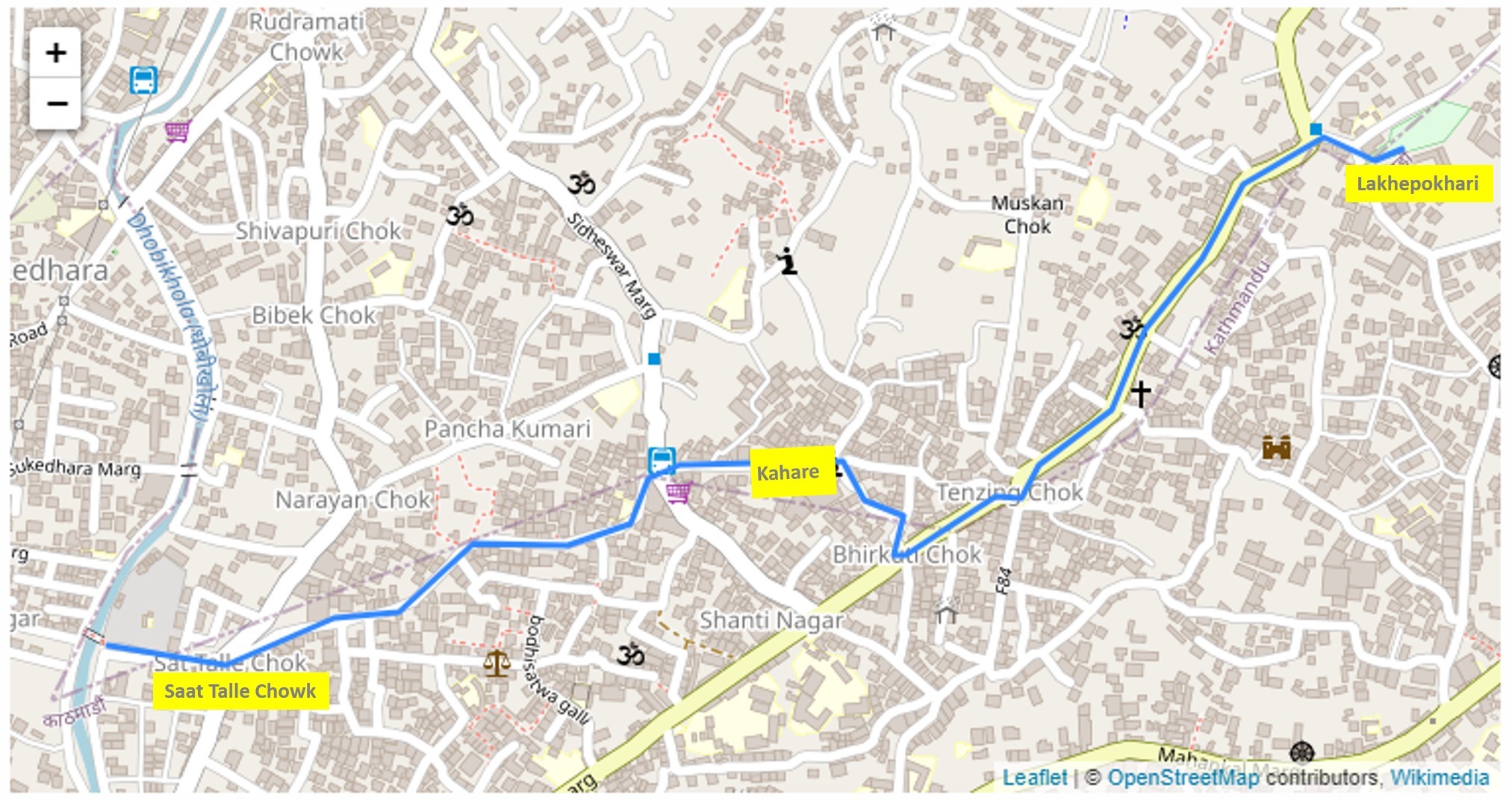

Another khahare khola divides Kapan’s Narayan Chowk from Boudha. Like the Holga meets the Bagmati, this khahare flows to the Dhobi Khola, one of Bagmati’s tributaries and is also interconnected with a pond, Lakhepokhari.

Just like the Holga was connected with Ghyoilisang pond, Lakhepokhari too was connected to Kapan’s khahare khola. These water resources fall under two jurisdictions – Ward No 6 and Ward No 12 respectively with a khakare khola dividing them. But these two interdependent ecosystems do not work as per the jurisdiction of the wards.

Chiranjibi Bhattarai, an advocate specializing in environmental law, has lived in Narayan Chowk for 30 years. Throughout the years, he has witnessed Narayan Chowk’s conversion from vast wetlands to concrete urban dwellings. When he moved to the area, there were very few houses. The earth was green and frogs croaked in the evening, he says.

Bhattarai says, “In the 1990s, building contractors and real estate owners saw these wetlands as wastelands.”

New residents constructed ‘pakki’ cement buildings and paved over the green wetlands. The houses became stronger, the waterways weaker.

In the monsoon, Narayan Chowk floods. According to Bhattarai, in 2020, when tenants who had left for their villages due to the Covid-19 lockdown returned, they found their apartments flooded with water. Potential buyers refuse to live in these houses and landlords cannot leave the area as there are no buyers for their property.

Bhattari’s son Ayushman jokes, “You trouble the khahare, the khahare troubles you.”

As the natural flow of the stream was destroyed, it was forced to break its banks. In response, the local municipality constructed concrete walls on the roads to prevent water from entering houses, a temporary measure. Residents and authorities both do not appear to realize that you cannot fight back against nature, which has a way of reclaiming its space.

An additional problem is that this stream flows through three jurisdictions of Budhanilkantha Municipality — Ward 10, Ward 11, and Ward 12. Shambhu Bhattarai, chairperson of Ward 12, blames a lack of communication between the various wards for the flooding.

“Without good communication, if one department constructs then another department excavates the same place after a few months,” he says. “The approach should be collaborative. This way, finances will also be used judiciously.”

In 2015, the earthquakes led to the collapse of a seven-storey building near Narayan Chowk. According to Ayushman Bhattarai, the building was bound to collapse as it had been built on the sandy banks of a khahare khola. But a few years later, two new buildings, one four-story and the other three have been built adjacent to one another. Locals still refer to this area as ‘saat talle chowk’ and in October 2020, when the lockdown was eased, a ‘7-floor café’ opened. The seven-story building might have collapsed but people’s aspirations haven’t.

Boudha’s future

The landscape of Boudha has changed drastically in the last 20 years. But Boudha’s modernization has come at the cost of a fragile ecosystem and traditional water resources.

The community, says Tashi Lama, knows how to pump groundwater but does not think of storing or recharging it.

“Residents need to find ways to recharge the earth before extracting water,” he says.

While constructing new buildings in Boudha, a small patch of land can be left open so that the monsoon water can seep into the earth, suggests Tashi. This is an idea that one of Boudha’s elected representatives is already considering. Dipendra Lama, chairperson of Boudha’s Ward No 6, knows very well how the area’s rivers are turning into sewers.

“I want to make it compulsory to plant at least one tree on any new plot of land where a building is being constructed,” he says.

Boudha’s water sources are equally a part of the Kathmandu Valley’s heritage as its built structures. Existing water bodies need to be safeguarded at a policy level. Recognizing the dead Ghyoilisang pond as a tourist spot is not enough, say locals. Old names like Holga need to be taught in the local schools as even these names have their own history.

Mukta Tamang stresses that the deterioration of the physical environment can also result in the destruction of the social and religious environment. In the book, Boudha: Restoring the Great Stupa, Ram Gopal, master mason for the reconstruction of the stupa after the 2015 earthquake, says, “Should there be another earthquake, this stupa will withstand it because it has been built strong with a pure heart.”

But, without water, there can be no purity.