As a young girl who was born and raised in the alleys of Bhaktapur, the Falchas there were my playground, my refuge and my shelter. Almost every day after school I used to rush over with some neighborhood friends to play chungi or gatti or to just chat for hours and hours, until we lost track of time and mother’s shout would remind us of the homework we needed to finish before dinner. While us children were in school, the Falcha would not be empty- grandparents would gather to discuss the news and politics or simply talk about life, the stray dogs of the neighborhood would be fast asleep in the corner, young men would meet up to play passa, and if a new visitor was passing through, they would be resting. Even in the monsoons when it would be raining cats and dogs, we would rush to the Falcha for shelter and make paper boats to watch them sail over the drainage channels.

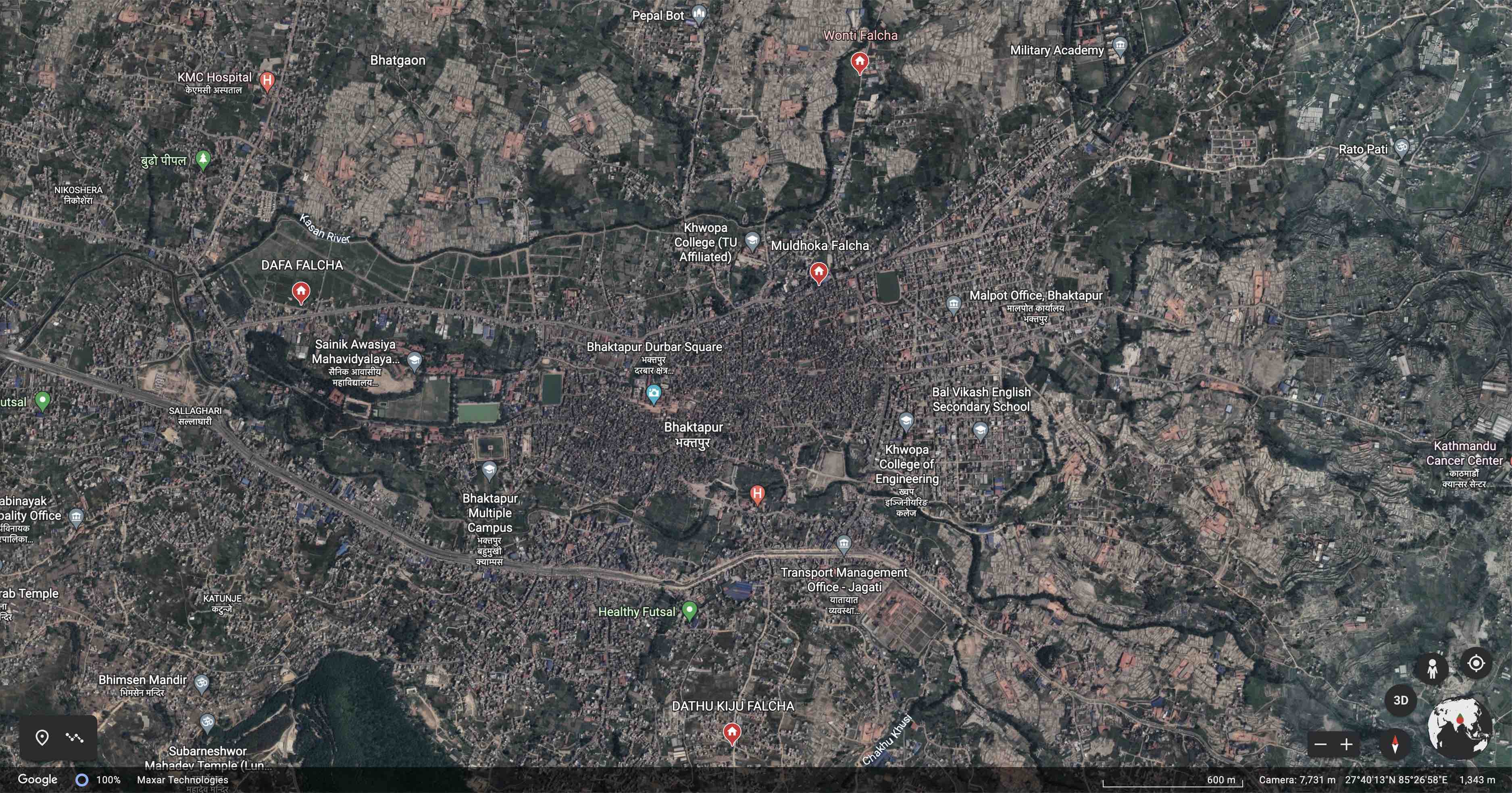

Commonly known as Patis, Falchas are well respected as communal spaces that serve various roles from being a place to hold meetings to an important space for festivities and celebrations. As I have grown up I’ve witnessed a gradual shift in the way that Falchas function and the way it’s treated. It’s barely recognisable to the space I grew up in, not just in terms of the physical materiality of it but also the general attitude towards it. I took KVUHP as an opportunity to understand this shift within the historical context of the value placed on these Patis/Falchas. During my field research when I began going to Falchas in different locations, I noticed a distinct difference between the ones within the core Bhaktapur city and ones on the outskirts. This made me further question the importance (or lack thereof) of public spaces, the issues regarding the ownership of these spaces and the tension between heritage for tourism vs. heritage for the people. Taking four Falchas and looking at their past and present situation through comparative study, I have attempted to explore these questions.

Dathu Kiju Falcha, named after the guthi responsible for its preservation, is located in Sipadol on the way to Doleshor Mahadev Temple. Barely visible under a thick layer of dust, surrounded by unkempt shrubs and with an electricity pole placed right in front of it, passersby barely visit this neglected Falcha. Wider road construction seems to be the main reason for its neglect and also a drainage channel that has literally blocked the way to enter the Falcha.

‘Dathu’ means ‘middle one’ in Newa language. However, the ones on its either side have been destroyed for the sake of urban development projects. The reason the middle one still stands is because the guthi works at least once a year for its preservation.

The area surrounding Dathu Kiju used to be agricultural fields just few years ago. Farmers would use it as a resting place to avoid heat stroke during the summer or to escape the thunderstorms during the monsoon and wayfarers would use it as an overnight shelter. But with rapid urbanization, the land prices went up and many farmers sold their land which led to this area being submerged with concrete buildings. While the guthi still visits Dathu Kiju once a year to celebrate its anniversary, because of a lack of budget, they are not able to prioritize a complete restoration of this space.

Dafa Falcha in Sallaghari is similarly abandoned like Dathu Kiju. Indrani Dafa Bhajan guthi members visit annually to clean the Falcha and remnants of tika on the pillars suggest that they also perform some religious puja there; however, that is barely enough to sustain for the rest of the year. The 2015 earthquake destroyed this Falcha and in its aftermath the old brick roof got replaced by a tin roof.

As Kathmandu City expanded New Town Planning came into the picture from 2014 in Bhaktapur and plotting of old farm lands for new settlement through land pooling took precedence over preserving public spaces.This was a profit driven initiative without any sustainable environment or heritage preservation goals. The aim was to simply plot and sell any empty space for housing. Such reckless planning is the reason why we see communal spaces like Dafa Falcha slowly disintegrating.

Kaji Lal Boyaju, who is the head of Indrani Dafa Bhajan guthi, still remembers waiting at the Falcha for his friends to walk along the fields. He remembers how they used to gather there to listen to bhajans during festivities or how people traveling to Kathmandu from Bhaktapur would rest there, drink water from the dhungedhara nearby and talk about their journeys.

Destroyed in the 1934 AD earthquake, the Falcha at Muldhoka is in complete ruins. At the entry point to Bhaktapur for people coming from the east, this Falcha functioned as a trading hub for Tamang men and women from Kavre and Panauti selling wood used as pillars for Newa houses, various utensils and vegetables. They stayed in this Falcha for as many days as it took to sell all the things they brought. This was a perfect location for the travelers staying overnight because of the Gonga Pukhu and the Dhungedhara.

Even with a car parked above the remains of this Falcha, it was fairly easy to identify because the stone Naga (symbolisation of snake and water) and brick Kashimo (lotus flower) which was the base, is still there.

In some ways it is inevitable for new modern developments like a vehicle road to replace old spaces like Falchas used mostly by people traveling on foot. However, having said that, it’s important to recognise the loss of intangible things like a sense of community, a sense of public space and heritage and history that these spaces hold.

Wonti Falcha, on the way to Changu Narayan, was also abandoned after the 2045 BS earthquake. Similarly functioning as a shelter for travelers, a temporary storage facility for farmers’ grains or for communal meetings, this Falcha was like the others in the past. In the present however, unlike the other Falchas mentioned above, this one has been completely renovated under the supervision of Bhaktapur Municipality. In addition, other Falchas on route to Changu Narayan Temple have been recently renovated.

This made it apparent that these specific Falchas were renovated because of the title Changu Narayan Temple holds as a ‘World Heritage Site.’ The priority for renovation from the Municipality seems to be promoting tourism over conserving communal public spaces. When the authorities themselves see the value of these Falchas only in tourism, it would be unreasonable to expect new residents of the area to understand the history and social importance of these spaces. This is an alarming trend where we are not even aware of the history that is being lost. If we know our history we know what we can rightfully claim as public, otherwise we slowly forget our sense of community and identity.

It is important to note that many Falchas in Bhaktapur have been fully renovated and still function as a communal hub. There is still this sense of common ownership of this space; a space that is multifunctional and open to everyone. People still come together to renovate the space as needed and use it as per their needs. Even if it is on a smaller scale, it’s still inspiring to see some of the older values about a public way of life still persevering within the chaos of capitalism. A loss of public space is a loss of public sense.